Friday, 01 December, 2017

It´s a matter of gradients

Origin of life

Thermophoresis for the energy supply of early cells. CeNS member Dr. Christof Mast and his team suggest thermally driven formation of pH gradients and proton flux as source of chemical energy conversion in early stages of life.

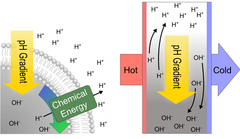

The transport of positively charged protons along a pH gradient serves to generate energy in cellular systems where membranes maintain the gradient. Without a membrane containing highly developed pump proteins, it will be difficult to prevent protons from rebalancing their concentration in the liquid immediately. A team led by CeNS member scientist Dr. Christof Mast in Professor Dieter Braun's research group has discovered a process that can produce pH differences even without membranes only with the help of a heat flow through a water-filled pore. Thermal energy is converted into chemically usable energy.

"Living cells use pH differences as the universal driving force of their cell power plants," explains Mast. Approximately four billion years ago, before the evolution of proton pumps, other mechanisms were needed to generate pH gradients. "On the early earth, thermally driven formation of pH gradients could have been achieved near heat sources in porous rock," adds Lorenz Keil, the first author of the publication in Nature Communications.

Proton flux as source of energy

Similar to the energy generation from water flowing along a height difference in hydro power stations, cells can produce chemical energy by the controlled equalization of protons along a pH difference through a membrane. Such pH differences also played an important role in the evolution of the most important molecular building blocks of life, such as ribonucleic acid (RNA) and various amino acids on the early earth.

The heat flow, as it occurs for example in oceanic hydrothermal fields, creates a temperature difference between the opposite sides of the pore and causes two decisive effects: biomolecules migrate through the so-called thermophoresis along the temperature difference to the cold side. At the same time, a convective flow develops in the pore by the sinking of the slightly denser water on the cold side and the rise of the lighter water on the hot side. The interaction of both mechanisms concentrates higher charged molecules on the bottom of the pore. There, they can absorb free protons and thus establish a higher pH compared to the upper regions of the pore.

Motor of the first cells on earth?

Driven by thermal convection, the first cells could have cycled between regions with different pH-values. The comparatively fast transport of vesicles could cause a proton gradient across proto-cellular membranes, which is done by sophisticated proton pumps in their modern relatives. “Applying this method would have enabled early cells to generate chemical energy without the need for actively driven proton pumps," said Mast summarizing their findings.

A simple difference in temperature constituted not only a helpful tool for the formation and multiplication of the first biomolecules, but could also have driven the metabolism of the first cells.

Publication:

Keil LMR, Möller FM, Kieß M, Kudella PW, Mast C: Proton gradients and pH oscillations emerge from heat flows at the nanoscale; Nature Communications, 2017 Dec 1; doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-02065-3

Contact:

Dr. Christof Mast

Systems Biophysics

Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München

Amalienstr. 54

80799 Munich

Germany

Tel: +49 (89) 2180 – 1484

E-Mail: christof.mast(at)physik.uni-muenchen.de

Web: www.biosystems.physik.lmu.de/people/index.html